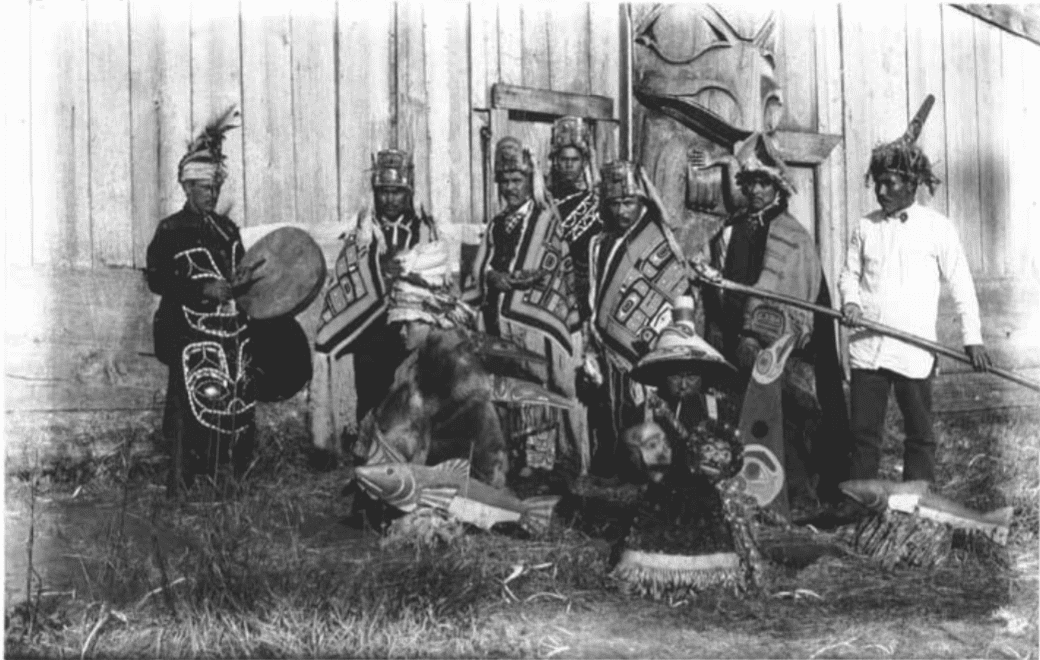

From towering totems to giant 60 foot cedar canoes to the architecturally elegant clan houses to the crackling fires inside them, perhaps no other indigenous society enjoyed more of what nature could provide than the Natives of the Pacific Northwest coast.

They had trees. Big trees. Lots and lots of big trees.

Trees for Transportation

The giant red cedar canoe was central to the advancing and thriving of indigenous people as glaciers retreated to their mountain lairs after the last ice age.

Access to big trees for transportation, and everything else that comes with it has shaped their culture ever since.

Their great red cedar canoes allowed SE Alaska’s ancestors to expand their range and establish villages with the best access to the most important resources – including big trees.

Places like Taan.

Home for Trees

Taan, (Prince of Wales Island) is a traditional Tlingit stronghold in southeast Alaska. It’s the fourth largest island in the United States, after Hawaii, Kodiak and Puerto Rico.

And it grows some of the worlds largest trees.

But Taan is not all Tlingit. The village of Hydaburg is traditionally a little Haida hideaway where locals still practice traditional Haida ways.

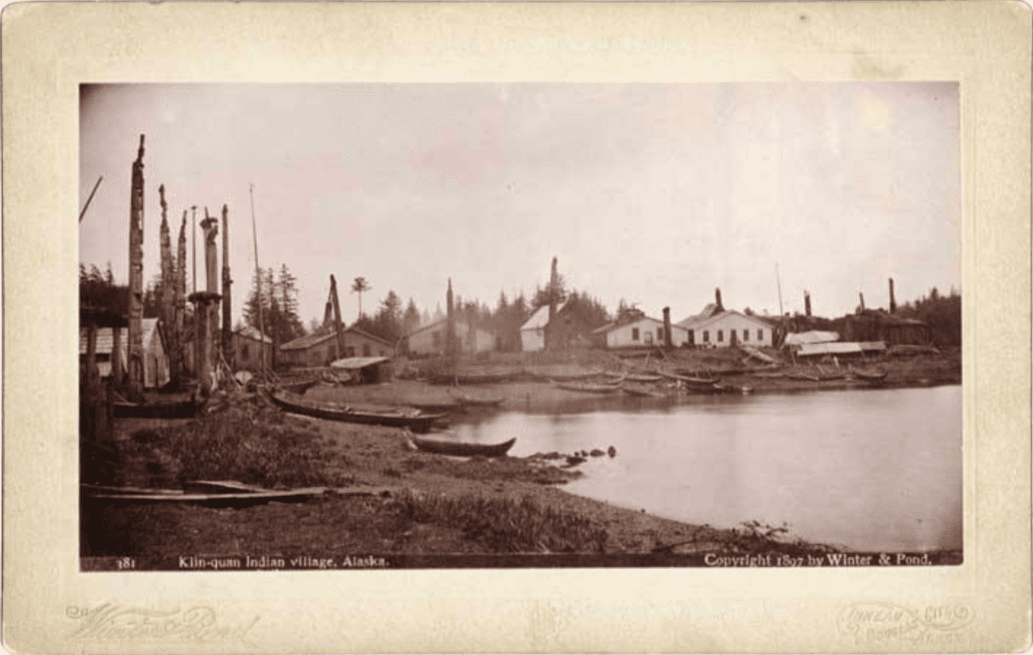

Before the beginning of the 20thcentury, waves of cultural and economic change washed over the old villages and the old ways in southeast Alaska, including three historic neighboring Haida villages: Howkan, Sukkwan and Klinkwan

Mobile Homes

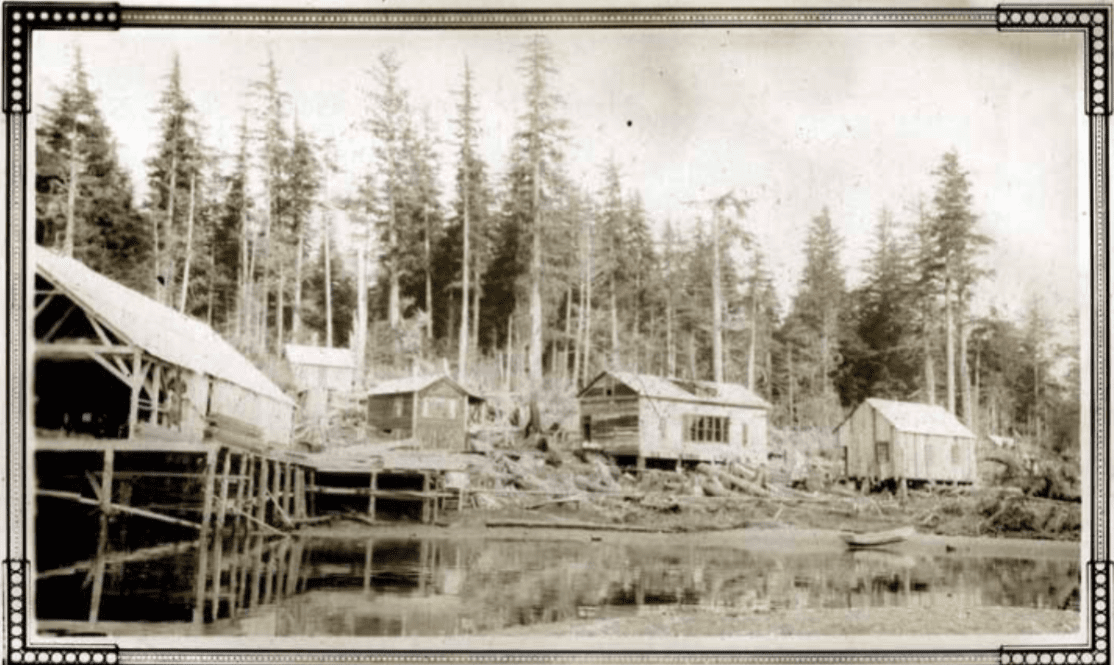

By 1911, the three villages consolidated and moved their houses, people and resources to a new site with good water on the southernmost tip of Taan.

Stronger together, the three Haida villages were better able to weather the storms of cultural and economic change from their new location – Hydaburg.

Moving village sites isn’t new to the indigenous people of SE. Traditionally, when resources for heating, shelter or food became harder to gather close by, or conflict or disasters visited, other desirable sites were sought and established using much of the actual building materials from the previous site.

Trees for Homes

By fitting the precious vertical wall panels into slotted horizontal beams and sills, the long houses were designed for relatively easy dismantling, moving and reassembly – certainly easier than fabricating new panels each time they moved.

That’s because each tree, board and beam was hand harvested and hewn with effort and care that represented much more than merely the wood from which it was made

Carved house posts and the totems in front of the clan houses were similarly imbued with the spirit of the tree and the carver, often remaining after the rest of the home was relocated.

Old Ways

The majestic Spruce, Hemlock and sacred Cedar trees that once carpeted Taan, supplying shelter, transportation and heat for millennia, eventually yielded to industrial harvest in order to build the canneries, mines, docks and communities arriving with each new stream ship.

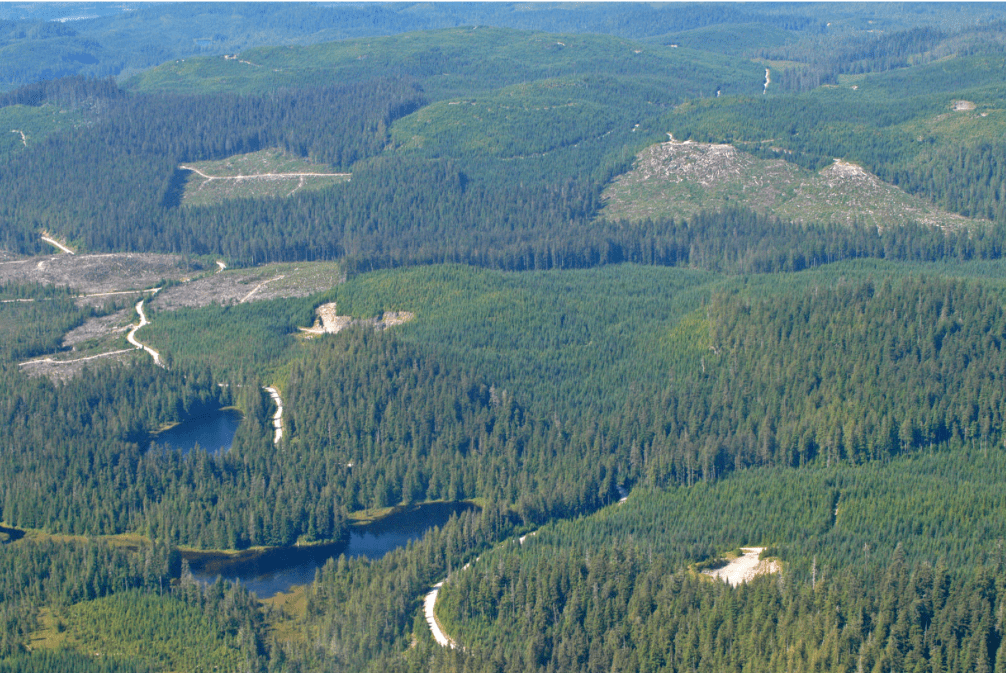

Apart from a few small independent sawmills, hundreds of miles of roads and thousands upon thousands of acres of trees in various stages of regrowth, little remains of the once voracious timber industry that boomed, then busted as big trees became scarce.

New Ways

And apart from old photographs and a few preserved totems, little remains physically of the old clan houses and great canoes.

But the traditions remain and new longhouses are rising in communities as a new generation labors to preserve their culture.

By sustainably harvesting local timber and employing local artisans, villages are re-assembling their past using the precious cultural and natural resources they have known since time immemorial.

Now new Eagle and Raven totems stand guard in front of the new Hydaburg Clan House, representing Haida efforts to seek balance in their culture – balance between clans and balance between old ways and new ways.

Trees for Culture

Stories and sculptural art are a mainstay for most cultures, including SE Alaska Natives who have fused the two art forms seamlessly into their totems.

Along with the resurrection of clan houses across SE, is an accompanying renaissance of traditional arts – often practiced in community carving sheds where elders pass on the stories, wisdom and skills to those who follow.

2018 SSP visitors to Hydaburg were invited to touch the spirit of the wood revealing the eagle beneath the artist’s chisel. This totem is standing on the right in the clan house photo above.

Trees for Heat

On a predictably unpredictable March day in southeast, Michael Sheppard, Taylor Asher and I all managed to arrive on schedule at the Klawock airstrip to be swept-up by the indefatigable biomass energy director for Southeast Conference, Karen Petersen. She organized the agenda and gatherings we’d be attending over the next couple days.

Karen is one of Alaska’s noted leaders in the field of renewable biomass energy. She and her semi-famous husband Jim Baichtal, live on Taan in the formerly bustling logging camp called Thorne Bay.

Michael Shephard is the Deputy Director of Forest Service State & Private Forestry. Taylor Asher is the biomass program manager at Alaska Energy Authority. I am the REAP Energy Catalyst for the Sustainable Southeast Partnership.

We were all visiting Hydaburg to celebrate the official commissioning of their brand new Garn cordwood boiler system, installed to heat Hydaburg school buildings.

Why Heat With Wood?

Remember that logging camp-turned-community mentioned earlier? Thorne Bay is just one of many vestiges of Taan’s industrial scale logging heydays.

A few minutes on Google Earth reveals a dense network of hundreds of miles of old logging roads among thousands of acres of clear-cuts in various stages of regrowth.

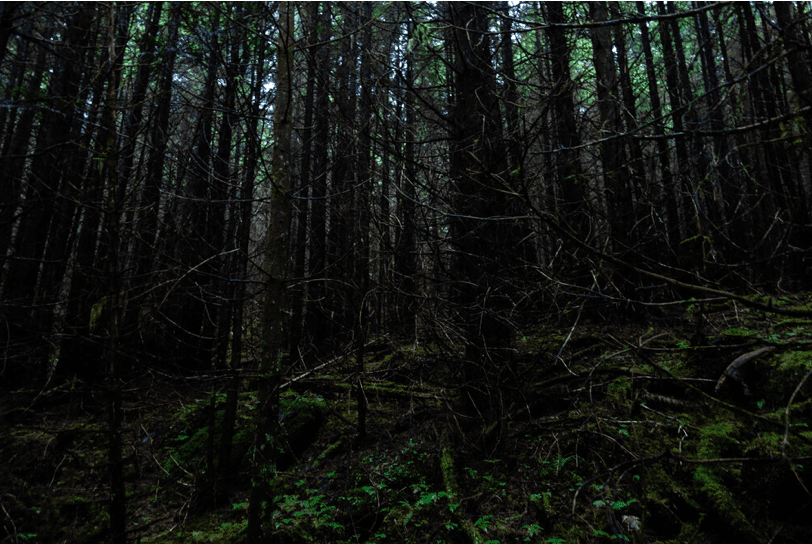

Wall of Wood

Left unattended in SE, new growth timber is nothing like a living, diverse forest. It’s more like a dense, dark thicket with all the skinny trunks growing too close to each other to get sufficient light. The result is a timber stand that lacks value either as an ecosystem – or for lumber.

Using low-grade forest thinning, harvest residues and mill waste for heat instead of oil creates a more healthy and sustainable forest ecology and economy.

For small remote SE communities with high energy costs and miles of old logging roads, this wall of densely packed small trees is both an ecological problem and an energy solution at the same time.

Communities like Hydaburg.

Stoked for Wood Heat

Fortunately, Hydaburg is not the first village on Taan to decide to use wood to displace oil to heat their school. They had the advantage of watching their neighboring communities in recent years reap the economic and ecological benefits of using low-grade local forest thinning residues and sawmill waste instead of imported oil.

Craig, Klawock, Kasaan, Thorne Bay, Whale Pass, Naquati…and now Hydaburg, are all now paying locals to supply wood, thus keeping energy money circulating in the local economy longer, with the added benefit of using renewable energy to displace fossil fuel.

How Much Wood Would…

Question: How much wood would a wood-chucker chuck if a wood chucker could chuck wood – instead of burning imported fossil fuels?

Answer: 200 Cords in Hydaburg

Hydaburg schools were burning an average of 24,000 gallons of heating oil annually. By chucking 200 cords of locally sourced cord wood, the school can also chuck its oil bill – saving at least $30,000 a year in fuel costs.

At $200 a cord, Hydaburg’s energy needs are easily met by local suppliers, thereby strengthening the local economy while creating greater value for the resource by using otherwise unmarketable residual wood.

200 Cords of Locally Harvested Wood = 24,000 Gallons of Imported Oil

Tlingit – Haa Aani

Haida – Íitl’ Tlagáa

Tsimsian – Na Laxyuubm

Honoring & Utilizing Our Land

Honoring & Utilizing Our Land

For Tlingit, Haida or Tsimsian people, Honoring & Utilizing our Land is a cornerstone of their culture, acknowledging their dependence upon and obligation to the lands and waters that sustain their lives and culture. Making full use of everything they harvest is part of how they honor and respect their ancestors, culture and land.

It makes good sense that many remote Alaska villages are (re)turning to wood heat systems to heat their schools and other public buildings using timber harvest residues and sawmill waste instead of imported oil. Each BTU of energy produced locally is one BTU closer to energy independence.

This is how Hydaburg is achieving energy independence – the Haida way.

SSP – Wooch een

Wooch een is a Tlingit phrase which means working together. It’s used when there’s hard work for the community to do – raising a totem, placing a house post or hauling a giant cedar canoe up the beach.

Or hard work like finding a path forward economically while preserving control over aspects vital to their culture and resources.

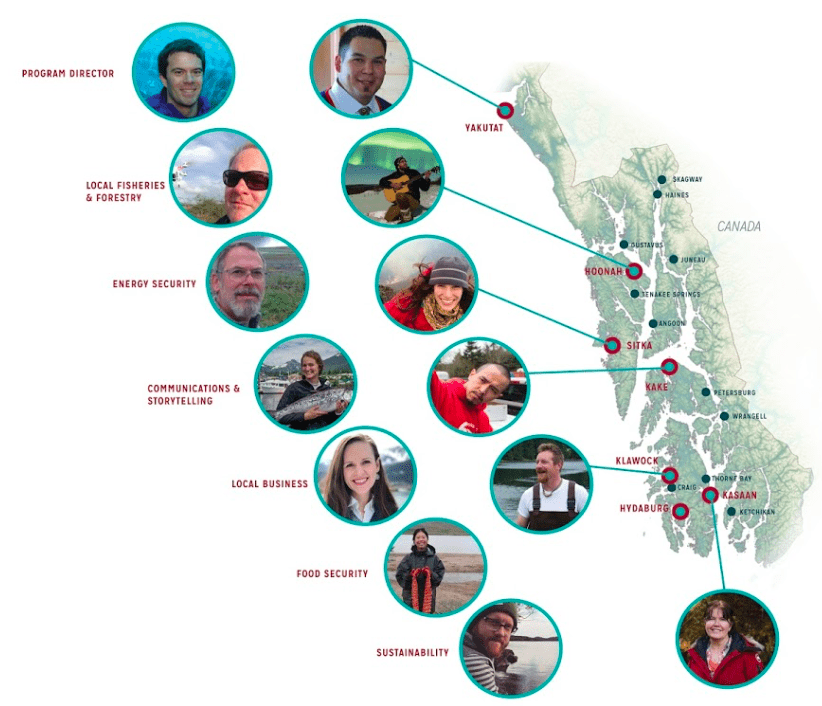

Working together is also the approach of the Sustainable Southeast Partnership – a diverse network of individuals and organizations committed to restoring and maintaining the ecologic, economic and cultural resilience of the region.

As the SSP Regional Energy Catalyst, I work on behalf of REAP to support and celebrate the efforts of SE communities seeking greater ecologic, economic and energy independence.

Communities like Hydaburg.

Planning innovative energy systems requires the time and energy of many participants Wooch een: – Hydaburg School District, USFS, Coffman Engineering, Alaska Energy Authority, Southeast Conference, REAP and other SSP Partners.