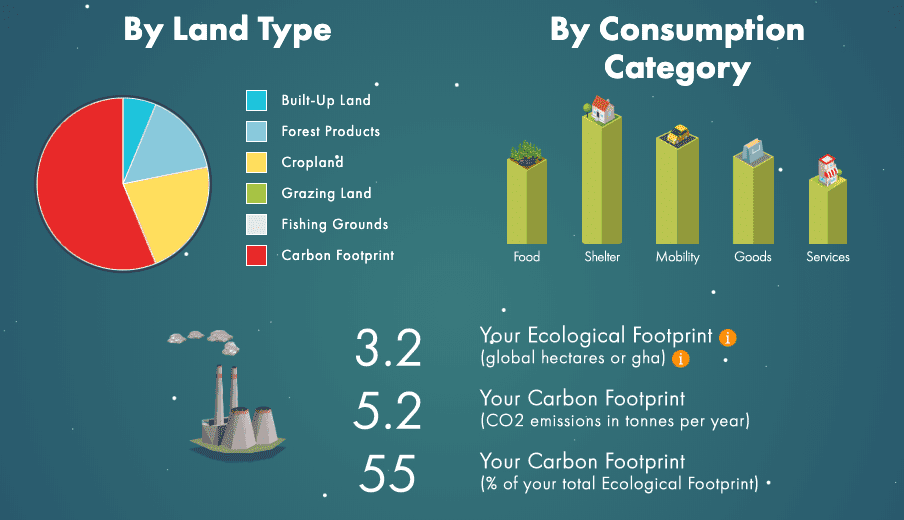

Essentially, by forfeiting air travel, I slashed my carbon footprint by about 60% and saved the world a whole lot of resources. Now I can see why Greta Thunberg is electing to travel by sailboat instead of plane.

At REAP, we often frame our teaching in the context of energy literacy, which is, according to the Department of Energy, an understanding of the nature and role of energy in the world and daily lives accompanied by the ability to apply this understanding to answer questions and solve problems. Our goal is to increase the energy literacy of all Alaskans, thereby increasing human capacity to make informed decisions about energy. I think through this endeavor of quantifying my own energy use, I myself have become a much more energy literate person. Because if we don’t understand how we use energy, how can we start to solve the problems that surround and encompass our energy use?

Further, it’s easy enough to look at climate change as some distant problem that will ultimately be solved by a bunch of genius scientists in white lab coats, rendering us completely useless and simply along for the ride in the interim. While I may get complacent from time to time, I vehemently push against that notion. Our actions absolutely have an impact, and we can absolutely be a part of the solution.

How we become a part of the solution however, can be a very personal decision and won’t look the same across the board. Telling an Alaskan that they shouldn’t get on a plane to visit their family in the lower 48 or travel to Anchorage for doctor visits, for example, likely won’t go over well. And does being conscious of our energy choices have to come at an expense of quality of life? I don’t think so, but I also don’t think I have to travel across the country 5 times a year to be happy. I think I could reasonably cut that in half or more, and look into other ways to be more efficient in my travel, like choosing to bike to work instead of drive more often. There’s so many angles to go about saving energy and living more sustainably – from purchasing carbon offsets for travel (which REAP has recently decided to do), to investing in efficiency measures to save electricity and heat in your home. These individual choices are powerful and should not be underestimated, because collectively they can lead to systemic, positive change.

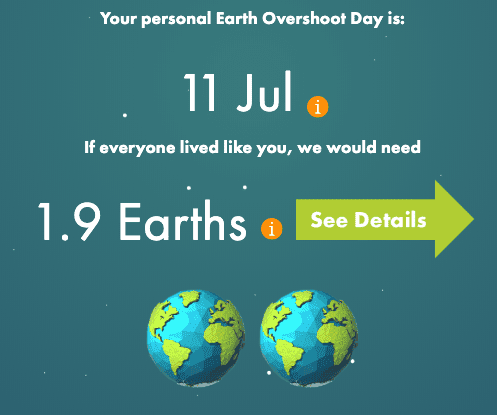

So how many earths does it take to sustain an energy educator for a year? Too many, but that’s not the end of the story – it’s just the beginning.