Get Involved!

If you want to help with Kiana’s project, get in touch with Chris McConnell at cmcconnell@realaska.org.

“Accessible only by plane or boat,” “roadless,” “the bush”—the usual descriptors for rural Alaska often proceed from the perspective of our state’s more populated centers.

These labels tend to emphasize the remote and isolated nature of village life in Alaska. In contrast, many of the Alaska Native place names used to describe traditional population centers invoke images of community and vitality. Kikiktagruk is the Inupiaq name for what most of us know as the Northwest Arctic Borough hub community of Kotzebue. The word can be translated as “almost an island” and “the place for meeting.”

This bit of wisdom is shared by a young computer science student and game developer named Kiana Norton, who lives in and has deep ties to the region. Kiana has been working with the Alaska Network of Energy Education and Employment for nearly a year to lay the foundation of a video game that combines her passion for technology with a deep appreciation for the unique experiences, perspectives and opportunities that go to the heart of living on “almost an island.”

We will be checking in with Kiana throughout the coming months as she leads a collaboration between industry (TotalView), utilities (Kotzebue Electric Association and Kwig Power Company) and others to create a game she is calling “Inuelectrix.” Kiana conceives the game as an immersive, exploratory adventure that illuminates the challenges of maintaining and operating a clean energy microgrid in rural Alaska. ANEEE’s involvement with Kiana goes to our mission of highlighting the many career pathways that are opened up to all Alaskans through a greater understanding of energy.

Here is Kiana, in her own words:

The view overlooking Kotzebue. Photo by Kiana Norton.

Self portrait by Kiana Norton.

The sunset in Kotzebue. Photo by Kiana Norton.

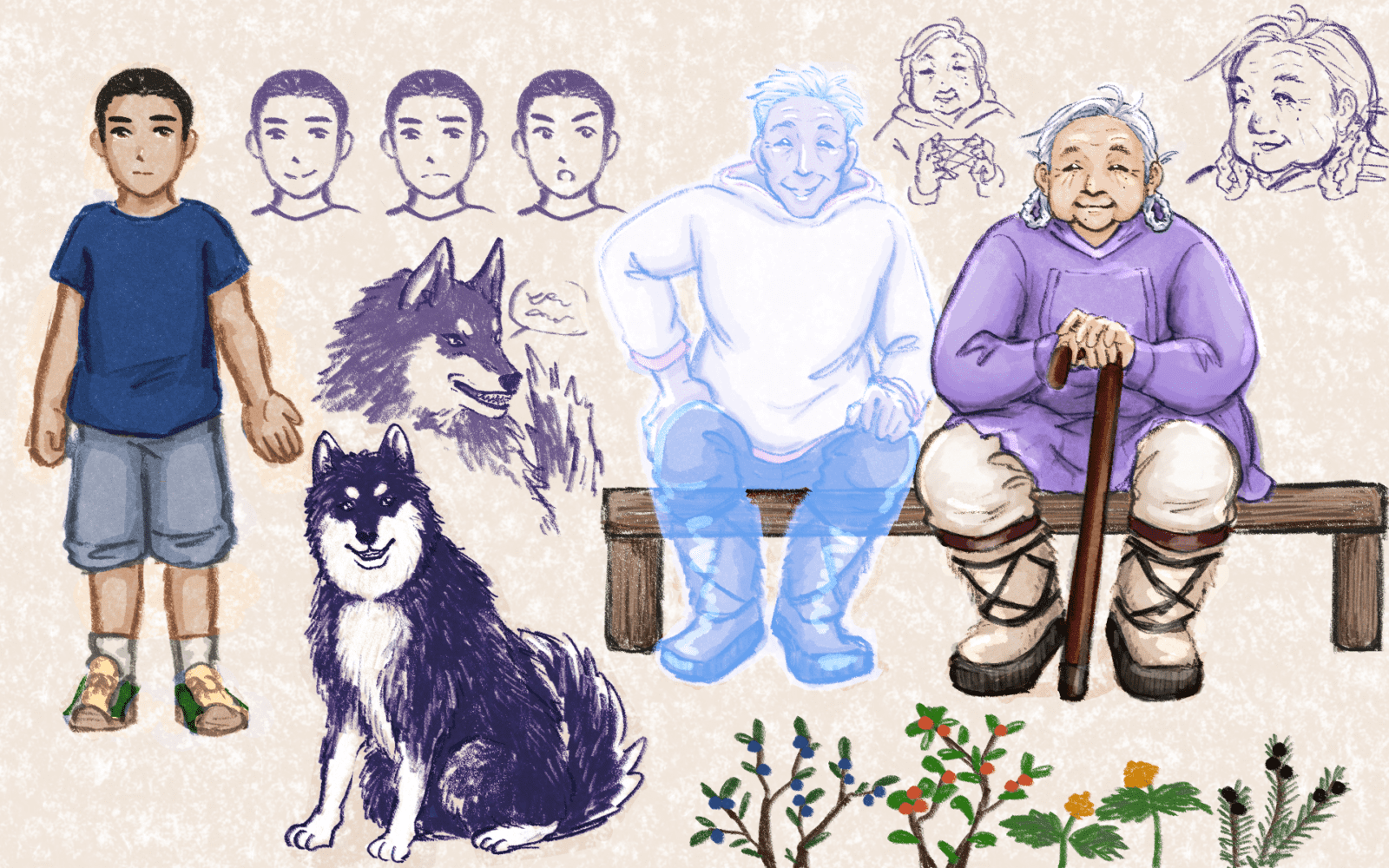

Illustration by Kiana Norton.

My name is Kiana Norton. I was born and raised in the small town of Kotzebue, Alaska. Kotzebue is a rather unique place. It’s named after the explorer Otto von Kotzebue, who came to the area in 1815. The area’s native name, Kikiktagruk, is said to mean “almost an island” and “the place for meeting.” This unique setting certainly led to an interesting childhood, and one I cherish.

Just like it takes longer to ship apples and other general goods to such a remote location, information, trends,and innovations take just as long to make their way here. It always felt like I was living in a place preserved in the past. While the internet and TV were able to keep us somewhat up to date on what was going on with the rest of the world, Kotzebue has always maintained a sense of community and tradition that makes it feel more like it did in the 1950s. People still hunt and fish, they still hold events like the blanket toss on the 4th of July, they participate in dog mushing and everyone knows all about you—if not personally, then by way of your parents.

It is easy to forget that I do not live in a past that the rest of the world has left behind. Our elders still tell stories of the olden days, when much of the town was still tundra, ice pulled from the lake was our water and the woodstoves in our homes left a smoke that hung everywhere over the ground and created an eerie fog. Whenever I hear these stories, they sound like fairytales from a long-gone time, but they are not that far in the past. My dad Ernie Norton is living proof. He’ll sometimes tell me about growing up in Kotzebue. The tundra was his playground, bees were his candy and most of their food came from subsistence activities like hunting or fishing. The electricity that we’ve come to know as a staple in our daily lives was barely a part of his childhood. For a few years, his family had a small wind charged car battery. It lit a 30-watt light bulb for about 2 hours a night. It was always sad when the bulb dwindled and finally turned off. That single bulb was all his family had until 1956, when electricity came to Kotzebue, and incredibly, the family could read books through the night.

My dad has many more tales like that, and I have a few myself, though not as dramatic. Much like my dad, I didn’t really grow up with technology. We had a TV and a computer, which were nice, but I often found myself running around outside fishing, looking for cool rocks on the beach or building snowmen in the winter. I didn’t even have a phone until I was in middle school—and then, it was a little flip phone hand-me-down that I used sparingly to text my friends. And that was all. My flip phone was no good when I went to college at Eastern Washington University, and I reluctantly entered the smartphone world. I was stubborn in rejecting the need for a technology upgrade—I was content reading books, drawing and being outdoors.

Admittedly, there has been a longstanding exception to my stubborn rejection of technology: a passion for video games and gaming. Through some strange happenstance, our household acquired a Nintendo 64. I was much too young to join in the games, but from the moment I saw my siblings playing a Pokeman game that I never learned the name of, I was in love. I wasn’t even playing with them, but I fully shared in their wonderment. All the game characters running around the screen, the fantastical stories they would weave, the energetic happiness visible in my siblings—I desperately wanted to join their fun. I eventually did, and I have never stopped playing or learning. There’s just so much possibility; so many stories to tell, so many fun characters to get to know, so many worlds to explore and so many varied play mechanics to master.

My love for games is immeasurable and inescapable; so much so that my dream is to become a game designer. When ANEEE Director Chris McConnell discussed the possibility of developing an energy literacy game using lidar and photogrammetry taken of Alaskan towns, I was happy to hop on board. Our goal is to make a simple game for all ages that will introduce people to the unique nature and role of energy within rural Alaskan towns. Many such towns, including my home of Kotzebue, operate as microgrids, unconnected to any other larger grids. The energy flowing through our microgrid needs to be generated entirely within Kotzebue. The challenges are immense, but so are the opportunities for independence and flexibility in our choice of power generation. Kotzebue and rural Alaska are leading the world in energy innovation.

Games and gaming provide an opportunity to explore and understand abstract hypotheticals that might be too dry or technical in other forms of media. It is my aspiration that Inuelectrix will be a game that brings fun, joy and insight to the world of energy in rural Alaska. Other games like Fallout explore the possibilities of an apocalyptic world no longer suitable for humans. Dynasty Warriors and Three Kingdoms utilize ancient mythology as the foundation for play. Return of the Obra Dinn teaches seafaring knowledge as a means to solve mysteries surrounding a cursed ship.

At the end of the day, video games are made by people, so there’s always bits and pieces of their experiences and knowledge scattered throughout the experience. The unique culture of my region will be at the heart of Inuelectrix; I will include Aanas and Taatas, Inupiaq values, stories and the sense of community that small villages possess. I hope to represent my culture in a way that reminds our far-away family of home and gives outsiders a better sense of what village life is like. It is unique, it is our home and it is our culture that I cherish as someone who has the privilege of living it.

If you want to help with Kiana’s project, get in touch with Chris McConnell at cmcconnell@realaska.org.